I’m not a doctor, a health care worker, or an epidemiologist. But I’m a citizen of New York City. And we’ve reached the first of probably many more terrible milestones. 1,000 people have now died here in NYC from COVID-19. I see a lot of people trying to minimize this milestone by comparing these 1,000 people to the number of people who die from cancer, heart disease, car accidents, and flu. What’s different? Am I qualified to say anything about it? Probably not, but here’s my take anyway.

There are plenty of reasons why this is different, but one is particularly important. It’s a surge, and we’re not equipped for it. Flu, heart disease, car accidents, and cancer are unfortunately, a way of life for us. We have dealt with these realities for quite some time, and we have committed huge amounts of money and resources and technology and infrastructure and jobs towards stopping them. But when a new kind of sickness and morbidity hits in concentrated amounts, quickly, our hospitals and their staff are experiencing an extraordinary surge. We are putting a lot of dedicated health care workers into harm’s way. And, despite the heroic efforts of these health care workers, we are objectively failing to provide a lot of people the standards of medical care they require.

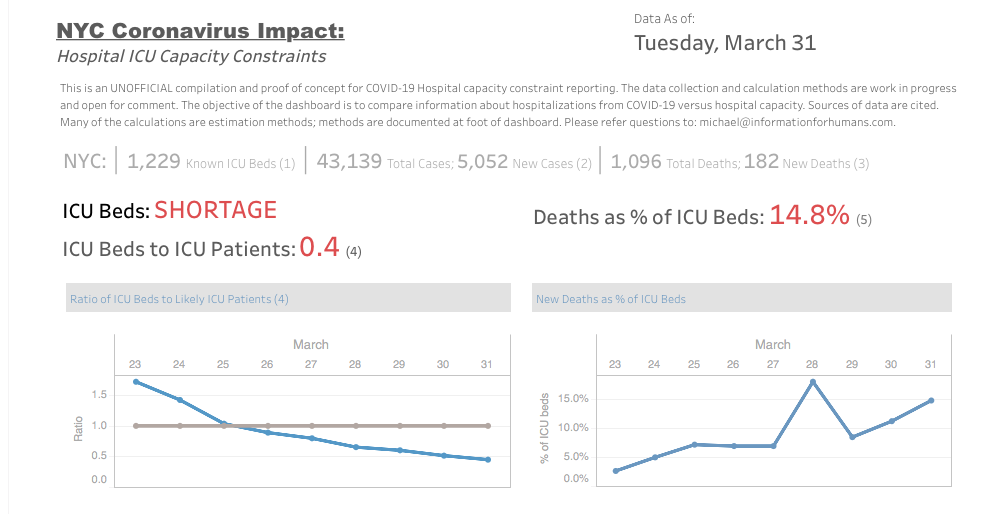

An important constraint on care giving is the number of beds in a hospital care setting that can provide ICU support. Depending on your source, as of the beginning of this year we had between 1,300 - 1,500 ICU beds in NYC. A complete description of the ICU requirements, and expansion of these requirements under emergency surges, can be found at https://www1.nyc.gov/assets/doh/downloads/pdf/em/icuce-tool.pdf.

Many of these beds were already occupied at the beginning of the year by people who needed ICU in the course of our normal lives: cancer, heart disease, car accidents, flu. But with our average deaths this week being 100-200 per day, and a caseload of over 40,000 people, the math plays out for professional care takers and amateur analysts alike: not enough ICU to support even that fraction of 40,000 people who need critical life-saving support. Right now.

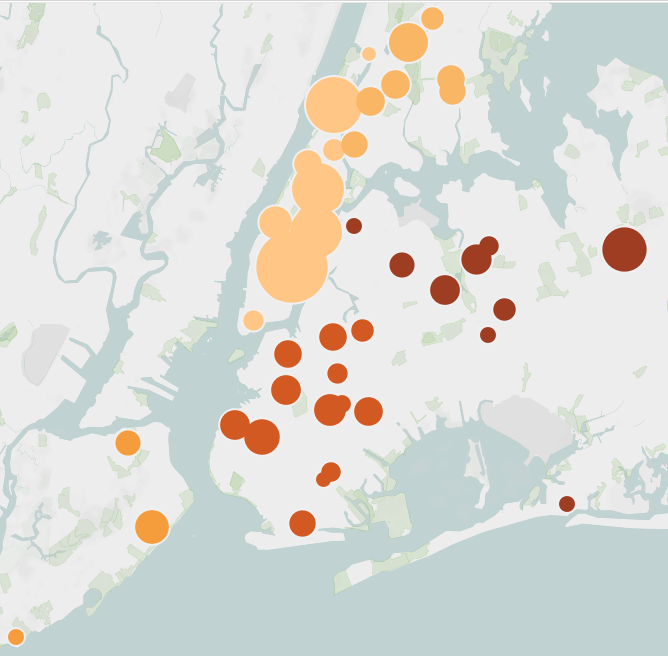

Ignorantly, but hopefully helpful, I pulled together some analysis, mostly for myself, that asked: where are our NYC hospitals? Are they evenly distributed through the boroughs and population so that the patient load would be evenly distributed? How many beds do they have, and of those, how many are ICU? The answer was: it’s bad. Hospitals are unevenly distributed through our geography and population, with some of the biggest concentration in Manhattan. Due to gentrification, demographics, and socio-economic factors, that’s a disproportionate allocation of ICU. People living in Queens and Brooklyn are in real need of immediate lifesaving care, and by the numbers, it’s harder to get.

My methods are probably off, the estimates are probably not good, but even with a lot of mistakes and ignorance, the picture is still pretty awful. We are asking health care workers to handle 2X -3X more dying people than what they are able to reasonably do. It’s heartbreaking for all of us here in NYC.

While this has been happening, I’ve been hugely privileged. I’ve been in my comfortable, safe Brooklyn apartment, well stocked with food. I haven’t been forced to go outside to get to work, and my work doesn’t put me in contact with others where I can either infect or be infected. I don’t have a mother or a grandmother living with me that I’d put at risk. My landlord isn’t trying to evict me. I’m benefitting from the law and order and safety that my local police force are delivering, while putting themselves at greater risk every day. I’m benefitting from the behind-the-scenes effort that my utility companies are putting in to keep our water running and our electricity flowing and our garbage collected. Yesterday I received a few admittedly non-critical food items from underpaid and underprotected Amazon workers. In New York City, my home, I’m alongside several million human beings who don’t have those things, and who, every day, still carry on in the face of it all, knowing the lack of those things could be their death sentence, or for someone they love.

I’ve put my name on many lists for volunteer opportunities. It’s probably a reflection of the heart and soul of so many New Yorkers that they haven’t gotten to my name on the list yet. And, it’s been a relief that at least one of my clients has now turned my work and theirs toward doing something productive about it. Instead of working here on abstractions for a life that’s been put on pause, I’ve been given a chance to work on things that will help people deal with this. That’s lifted me out of this disassociated despair I feel.

Meanwhile, the least I can and will continue to do will to be to update that analysis, and post it, daily. If nothing more, to remind myself of what’s going on outside, and the people who are risking their lives to keep us safe and well. And in the course of it, acknowledge somebody that may be tired, or may have fallen, in this fight. The daily candle is lit, here: https://public.tableau.com/profile/informationforhumans#!/vizhome/NYMetroIntensiveCareCapacity/Dashboard22?publish=yes